Foto Source: Artur Roman on Pexels

The Netherlands is moving steadily toward a sustainable economy. A crucial part of this transition is the bioeconomy: replacing fossil-based resources with renewable, biobased alternatives. Sascha Bollerman and Bernard van der Horst of the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Food Security and Nature (LVVN) discuss what the bioeconomy means, which dilemmas it raises, and the roles of both the Netherlands and Europe.

Sascha Bollerman works at the Department for Strategy, Knowledge and Innovation (SK&I) at LVVN. He first became engaged with the topic of the bioeconomy when he took over from a colleague in the working group on the bioeconomy in the European Standing Committee on Agricultural Research. Since then, he has served as the Ministry’s focal point on the topic and is part of an interdepartmental team working on biomass, bioenergy, and other biobased resources.

Bernard van der Horst is project leader of the National Biobased Resources Strategy at LVVN. As a member of an interdepartmental project leader pool, he coordinates this work on behalf of LVVN, the Directorate for Climate and Green Growth (KGG), and the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management (I&W). His task is to lead a broad team in developing a vision for 2050 that sets out how the Netherlands and Europe will shift away from fossil resources toward sustainable, biobased alternatives.

The term bioeconomy is used in many ways. How would you define it?

Bollerman: ‘To me, the bioeconomy is the specific part of the economy built on biobased resources - from farming and primary production to processing, trade, and consumption. These are resources of biological origin.’

‘That may sound straightforward, but the bioeconomy reaches into every sector. It involves not only farming and energy but also chemicals, construction, textiles, packaging, and transport. The bioeconomy runs through society. This breadth makes the field both promising and complex because every decision affects other domains.’

Van der Horst: ‘Until fossil fuels took over, the economy was entirely biobased. Now we need to restore a larger role for bio, but in a way that is sustainable and suited to today’s world. We are facing multiple global crises at once: climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution, including microplastics. Expanding biobased resources without limits would risk depleting the planet. The challenge is to identify what can be done sustainably—such as using waste streams, non-food crops, and solutions that retain as much value as possible.’

‘The bioeconomy therefore combines great potential with real limits. Because resources are scarce, policymakers must constantly weigh where they are most valuable. This scarcity makes the bioeconomy not only an economic challenge but also a deeply political and societal one.’

Bollerman: ‘Another factor is the relationship with the circular economy. The two are often conflated, but the EU makes a clear distinction. This year, the European Commission will publish an update on its bioeconomy strategy, and Member States are expected to align or update their national plans. For the Netherlands, the biobased resources strategy that Bernard and his team are developing will effectively become our national bioeconomy strategy. That gives it real weight: it is not optional, but a course we must follow.’

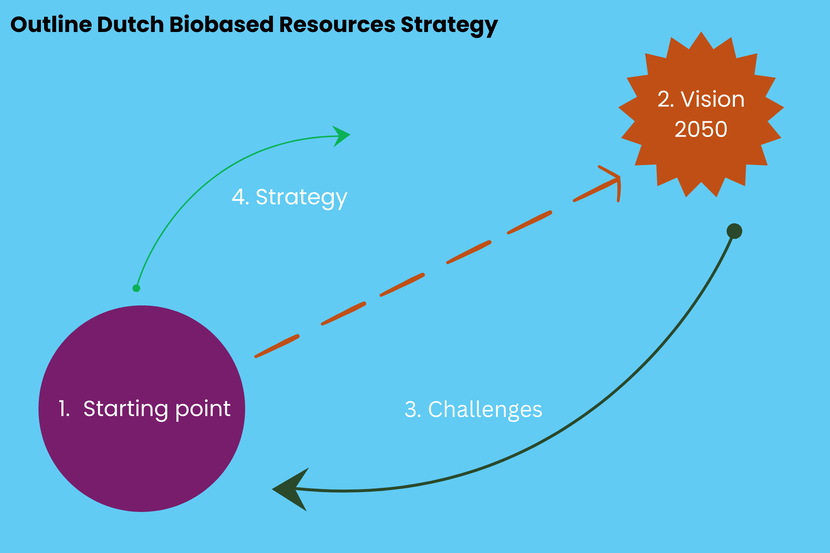

What are the main building blocks of the Dutch strategy?

Van der Horst: ‘The starting point is a long-term vision: what role will biobased resources play in 2050? From that perspective, we can work backward to identify the decisions we must take today. At the same time, the strategy maps out the dilemmas. In the past, the assumption was that food comes first, then materials, and whatever remains can be used for energy. That approach no longer works. Every domain is interconnected.’

‘Consider construction. Using more timber helps meet climate goals, but it also affects biodiversity and land use. Trade-offs like this are unavoidable. The strategy must clarify how the Netherlands will address them and what priorities we will set.’

Bollerman: ‘We also need to address geopolitics and import dependency. Where should the Netherlands source raw materials? How much should we produce domestically, and how much should we import? The energy crisis of 2022 showed how vulnerable dependence can make us. The same is true for biobased resources. A robust strategy must therefore combine sustainability with strategic autonomy.’

How far along are you, and who is involved in shaping the vision?

Van der Horst: ‘We are still underway. For example, several participation sessions have taken place, bringing together policymakers, universities, businesses, NGOs, and new networks. Participants were asked to share institutional positions as well as personal perspectives. That created very open discussions in which people were willing to think beyond their direct interests.

‘One theme that comes up repeatedly is the need to stay within planetary boundaries. This principle may sound abstract, but in practice it means designing the economy so that it operates within the Earth’s limits. Otherwise, we pass the costs on to future generations. At the same time, the Netherlands must build on its strengths: an innovative agri-food sector, strong research institutions, excellent infrastructure, and close ties within Europe. These assets give the country a strong base to lead, provided we make clear choices.’

Bollerman: ‘I see tremendous creativity. Stakeholders bring forward new ideas for value chains, business models, and unexpected crossovers between sectors. Think of links between agriculture and chemicals, or innovative uses of waste streams. This creativity shows that—with the right conditions—we can build real momentum. The energy is already there; what we need now is direction.’

Why is the bioeconomy such a priority right now?

Van der Horst: ‘Until recently, it was mainly seen as an opportunity: agriculture could produce additional things alongside food. It was a “nice-to-have”. Now it is a “must have”. The urgency has become undeniable. We must phase out fossil fuels, protect biodiversity, and reduce our dependence on external suppliers.’

‘The COVID-19 pandemic and the energy crisis following the war in Ukraine revealed how vulnerable supply chains are when resources come from abroad. Biobased resources are therefore not only about sustainability but also about security and independence. This is the moment to act.’

‘Biobased resources are not only about sustainability but also about security and independence’

Bollerman: ‘Europe plays a central role. As I said, the European Commission will update its bioeconomy strategy this year. This shows that the bioeconomy is not a passing trend but an established policy. For the Netherlands, aligning with Europe is essential, because only at the European scale can we create markets large enough to drive real change.’

‘This is where the Netherlands Agricultural Network (LAN), as representatives of our Dutch Ministry worldwide, comes in. The LAN teams collects knowledge and experiences abroad and brings them back to enrich our strategy. Different countries approach biobased resources in very different ways. Understanding those perspectives is vital.’

The Netherlands cannot produce everything itself and faces major environmental challenges. Where do the most important strategic choices lie?

Van der Horst: ‘I mentioned timber earlier, which is a good example. The Netherlands has few forests. That means we must decide whether to use them mainly for nature and recreation, or also for timber production. Another option is to recognize that our environmental goals leave little space for timber production and to source timber from elsewhere, for example from Eastern Europe where there is more capacity. These choices cannot be made nationally; they require coordination at the European level.’

‘And timber is just one case. The same logic applies to other crops and resources. We cannot prioritize everything at once. We must constantly weigh what to produce domestically, what to import, and how to make sure these decisions fit with our environmental and nature objectives, and our food security. That makes this both a strategic and a complex issue.’

How can the bioeconomy gain real traction?

Bollerman: ‘Laws and funding are important, but market dynamics ultimately decide whether the bioeconomy advances. A European consortium once developed an alternative to PET, the plastic used for soda bottles. The new material was more sustainable and superior products even stayed fresh longer. However, it has not succeeded yet, simply because fossil-based PET was cheaper.’

‘This example shows that little will change if biobased products cost more, and demand does not develop. Governments must therefore intervene, through taxes or regulation that make fossil alternatives less attractive. Such measures must be taken at the European level. Only with 500 million consumers can a market be created that is large enough to have real impact.’

Looking ahead: how do you see the future of the bioeconomy in the Netherlands and Europe?

Bollerman: ‘I hope that by 2050 we can truly say we have made the shift: that biobased resources sustainably and naturally form the foundation of our food system, our materials, and our energy. The Netherlands can play a leading role because we have strong research institutions and an innovative agricultural and industrial base.’

Van der Horst: ‘I see the bioeconomy becoming an integral part of our economic system. Now, our entire system is still built on fossil resources—from energy to recycling and waste processing. The challenge is not only to expand the bioeconomy but also to phase down the fossil system. That may be the greatest transition task of our time. But it is unavoidable—and essential—if we want a sustainable future.’

‘The real task ahead is not only to grow the bioeconomy but also to gradually dismantle the fossil system on which our economy is still built’

More information

Would you like to know more about how the Netherlands is shaping its bioeconomy strategy? You can send an e-mail to Sascha Bollerman: s.bollerman@minlvn.nl. Or to Bernard van der Horst: b.j.vanderhorst@minezk.nl.