Foto Pumalín National Park, Chile

The European Union's Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) will encourage Chilean companies to improve their transparency, traceability, and accountability. It also inspires them to strengthen their position in the global market as actors committed to environmental conservation and long-term sustainability.

In Chile, the history of deforestation presents a somewhat different and sometimes a contradictory narrative to that of other countries. For example, a major reason for the loss of native forest is the planting of fast-growing, non-native trees like Pinus insignis and Eucalyptus globulus. However, this was not the beginning of deforestation in the region. During colonial times, settlers cleared large areas of native forests, with estimates suggesting that two-thirds were destroyed by fires to make way for agricultural land.

Additionally, another cause of deforestation is the use of wood as fuel. This practice, vital for the subsistence of many small landowners, significantly contributed to the reduction of native forested areas across the country.

Subsidized commercial plantation benefitting the private sector

In 1974, the replacement of native forests with commercial species was encouraged through neoliberal policies of the Chilean Government, where up to 75% of the cost of new commercial forest plantations was subsidized, directly benefitting the private sector. The government took charge of the production of commercial tree species in public nurseries and planted on land that belonged to public as well as private entities. The government also helped build two major cellulose pulp production plants, Arauco and Celco, with significant investments from the Corporation for the Promotion of Production, the Chilean economic development agency. However, years later, these enterprises were sold to private entities at low prices, failing to recoup the initial government investment.

As a result of these policies, the government managed to turn Chile into one of the world’s lowest-cost producers of cellulose pulp (for papermaking). However, they did not consider how these low costs could impact the social and environmental costs underlying them. In 1983, experts were already raising apprehensions stating that the replacement of Chile's native forests with Pine insigne (Pinus radiata) plantations was a serious mistake, showing how poor management was risking natural treasures.

Increasing sustainable management of forest resources

Fortunately, the situation has changed. In 1998, the Law 19.561 prohibited the total or partial cutting of any native forest carried out without an approved management plan. Also, the replacement of native forests with exotic commercial plantations occurs less often, not only due to laws protecting native forests but also due to the incorporation of different certifications that forestry companies began to use.

Currently, Chile has more than 3 million hectares of commercial forest plantations, equivalent to 17% of its total forests (CONAF, 2021). These commercial plantations provide the raw material for approximately 97% of forestry exports.

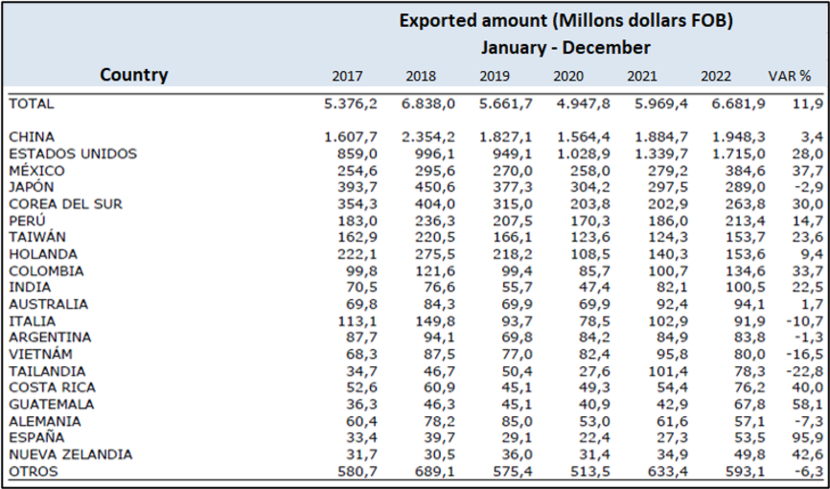

Table 1. Evolution of forestry exports from Chile, according to country of destination

‘In 1998, the government prohibited the total or partial cutting of any native forest carried out without an approved management plan’

As of 2022, the Netherlands ranks 8th among the countries that receive forest products from Chile reaching 153,6 million dollars. The main products exported to the Netherlands from Chile are bleached eucalyptus pulp, radiata pine plywood, coated multilayer cardboard, bleached radiata pine pulp and raw radiata pine pulp (Instituto Forestal, 2022).

Table 2. Products exports from Chile to the Netherlands

The EUDR strengthening Chile’s position in the global market

Chile’s most important forestry commodities are products with a low degree of transformation, such as round wood, chips, and sawn wood. How will the EUDR impact the trade of these products with the European Union? That is still difficult to predict.

For Chilean companies in the forestry sector, it is clear, however, that compliance with the EUDR presents both challenges and opportunities. The due diligence process may require significant investments in terms of human and technological resources to collect and verify the necessary information.

But there are opportunities, too. The EUDR can help Chilean companies improve their transparency, traceability, and accountability in the wood products supply chain. And perhaps, even better, it can strengthen their position in the global market as actors committed to environmental conservation and long-term sustainability.

‘Chile has more than 3 million hectares of commercial forest plantations’

More information

Would you like more information on the EUDR and how it will impact Chile? Please go to the country page of Chile at the website Agroberichtenbuitenland.nl of the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality. You can also send an e-mail to the agricultural team at the Dutch Embassy in Santiago, Chile: stg-lnv@minbuza.nl.

Bibliography

- Altamirano, A. and Lara, A. (2010). Deforestación en ecosistemas templados de la precordillera andina del centro sur de Chile. Bosque 31(1): 53-64.

- Carrere, Ricardo, (1998). Chile: Un modelo de plantaciones impuesto por el gobierno militar. Publicado en La tragedia del bosque Chile. Pag 285-293.

- Cornejo Esposito, Roberto (2015). La destrucción del bosque nativo en Chile. Sustainability, Agri Food Environmental Research 3(2), 30-32. ISSN: 0719-3726.

- CONAF, (2021). Catastro de los Recursos Vegetacionales Nativos de Chile. Actualizaciones al año 2020. Publicado noviembre, 2021.

- FSC, 2024. Forest Stewardship Council: https://fsc.org/en/newscentre/eudr/navigating-eudr-compliance-with-fsc.

- Instituto Forestal, (2022). Boletín Estadístico N 190. Exportaciones Forestales 2022. Verónica Álvarez González y Juan Carlos Bañados Munita. Área de información y economía forestal.

- Lara, A., Echeverría, C., Reyes, R. (2002). Bosques Nativos. Instituto de Asuntos Públicos, Universidad de Chile eds. Informe País. Estado del Medioambiente en Chile. Santiago, Chile. p. 127-160.

- Lara, A., Solari, M.E., Prieto, M.R. and Peña, M.P. (2012). Reconstrucción de la cobertura de la vegetación y uso de suelo hacia 1550 y sus cambios a 2007 en la ecorregión de los bosques valdivianos lluviosos de Chile (35° -43° 30’ S). Bosque 33(1): 13-23.

- Patagon Journal Magazine, Edición 18, primavera (2018). Available at: https://www.patagonjournal.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4172&Itemid=322&lang=en.