Foto The Netherlands Space Office

As global efforts intensify to halt deforestation, the Netherlands Space Office (NSO) leverages satellite technology to enhance compliance with the European Union's Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). Program Manager Ruud Grim sheds light on how Dutch organizations are using advanced earth observation to map deforestation, fostering innovative solutions that support the Sustainable Development Goals.

The NSO is the Dutch Government’s space agency. ‘We are not NASA,’ explains Ruud Grim. ‘NASA develops and builds satellites themselves, which we do not. In Europe, we collaborate within the European Space Agency (ESA). Our work revolves around supporting our space sector by fostering knowledge and stimulating development and innovation. We explore how we can contribute to society using satellite data.’

Earth observation technology offers insight into what is produced, where, and when

Grim leads the team that uses space to reach the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), hence his involvement with the EUDR. ‘The essence of the EUDR is to halt deforestation. Three actors are involved in this. Firstly, operators and traders, who must demonstrate compliance with the regulations. Secondly, the regulatory bodies, which in the Netherlands are Customs and the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA). Thirdly, the European Commission, which oversees the process.’

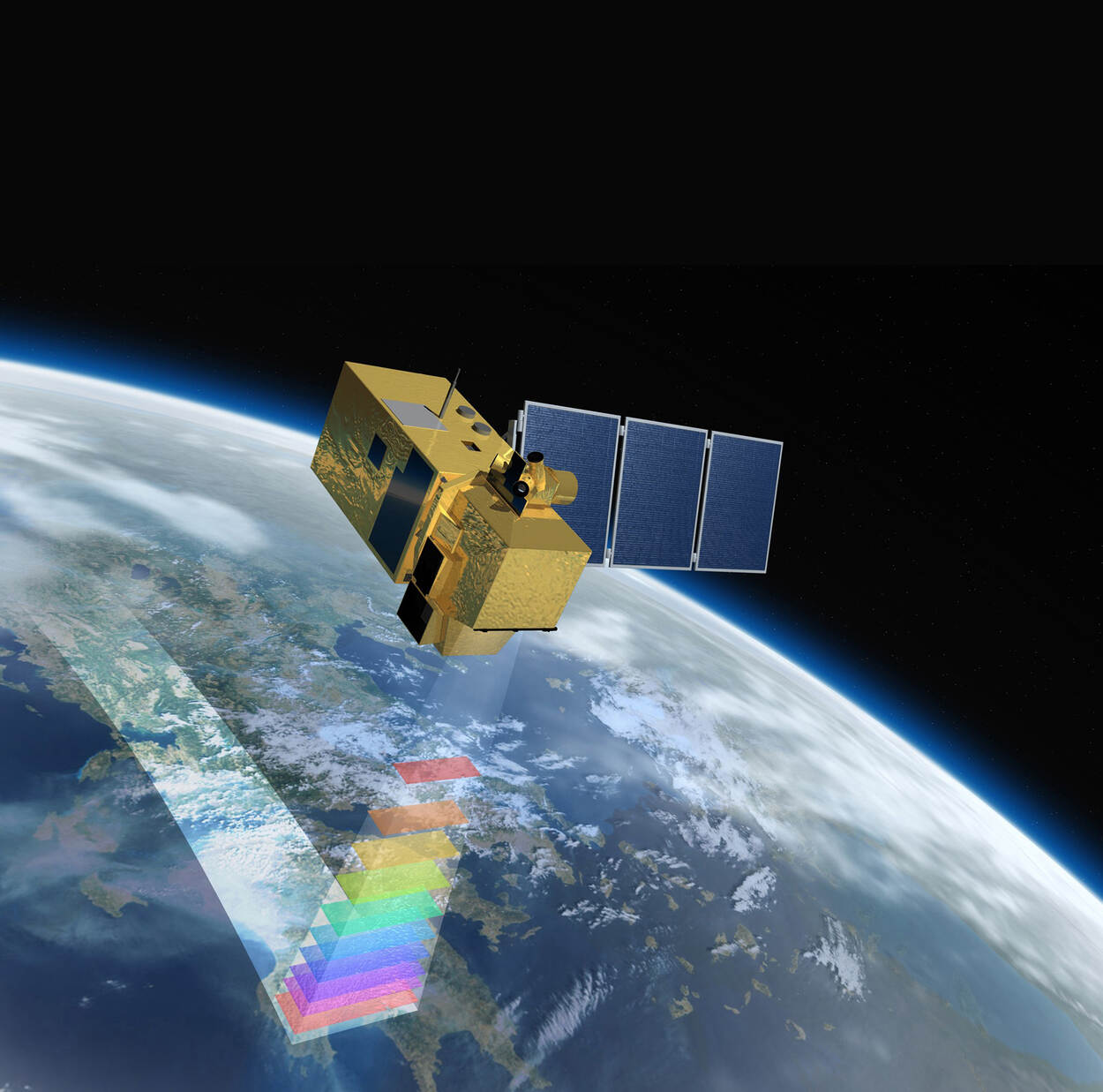

There is a connection to space at all these levels, says Grim. ‘The raw materials requiring EUDR compliance are sourced worldwide. From the ground, it's impossible to assess deforestation everywhere. Space provides a view from above: Earth observation. This perspective offers insight into what is produced, where, and when. The major advantage is that a satellite can observe large areas, and its use is consistent and transparent. Everyone uses the same Earth observation satellites.’

More information is needed than just a satellite image

Taking a picture from space might seem simple, but the process is more involved. ‘When you look at vegetation from space, you mostly see green. It is very difficult for a satellite to distinguish between different types of tree species and crops. This also means it's challenging to determine whether it’s a primary forest (a protected ancient forest) or a secondary forest (a regrown forest) with different regulations.

Taking multiple pictures over time can make this distinction, says Grim. ‘Additionally, ground information is required. What is grown where? Both for commodities grown on large commercial farms, such as palm oil in Indonesia or soy in Brazil, as well as for small-scale cocoa farming in Cote d’Ivoire, you need more information than just a satellite image. If there are multiple landowners and producers within an area, accurately knowing the boundaries becomes essential. If there are no cadastral data, you can solve this by simply having someone walk the borders to record the contours. There are small handheld devices for this nowadays – even your mobile can do it. This often uses the European navigation system (EGNOS), which is based on signals from both European (GALILEO) and American (GPS) satellites.’

For very small areas, a point location suffices. ‘What exactly is grown is known by the market parties and NGOs like Solidaridad, who work with small-scale food producers in developing countries. The challenge is to use all this information within existing local laws and European privacy regulations.’

The challenge is to use all this information within existing local laws and European privacy regulations’

European observation center for the EUDR

The European Commission aims to help countries set up a European observation center for the EUDR, based on both public systems, like the European Copernicus, and private systems. ‘But this still needs to be developed. Therefore, NSO advises the NVWA on the current possibilities to contribute to the EUDR. NVWA will likely act based on risk assessment and random checks, with more checks in areas with higher risks. Governments may use high-resolution satellite images made available through the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for inspections.’

Commercial intermediaries are also preparing for the EUDR. ‘These intermediaries take the technical and operational work off the market parties' hands. Satellite images are readily available – from the European Commission and companies like Google and Amazon. The same applies to the techniques. Gathering ground information poses the biggest challenge, yet it remains achievable. It just requires good cooperation with local parties, governments, and NGOs.’

Inspiring Dutch companies

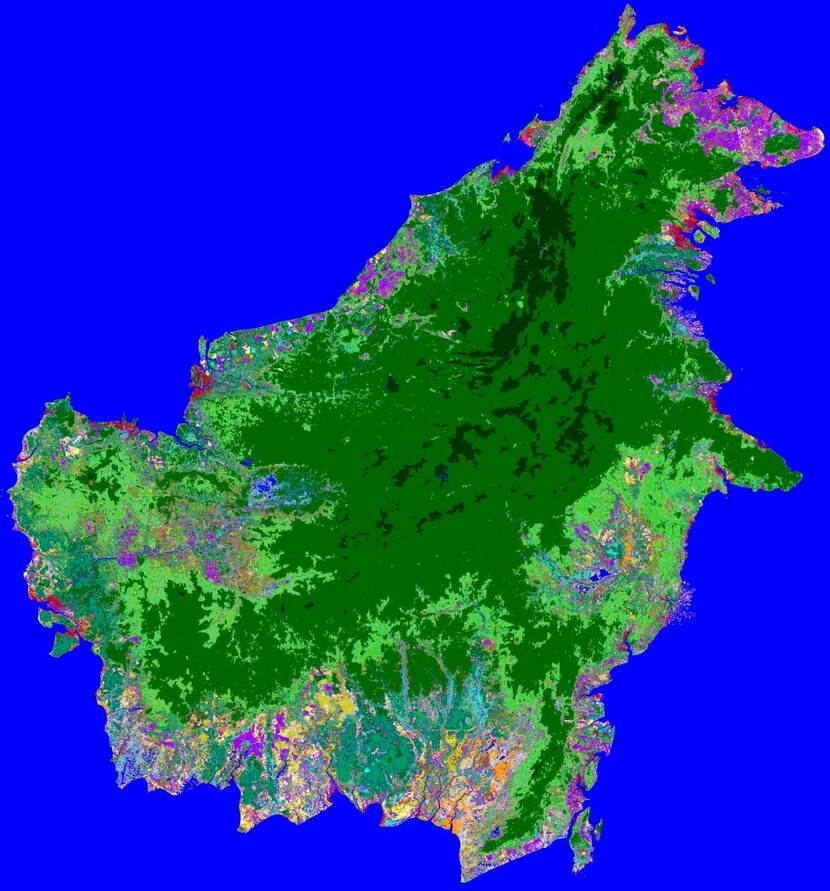

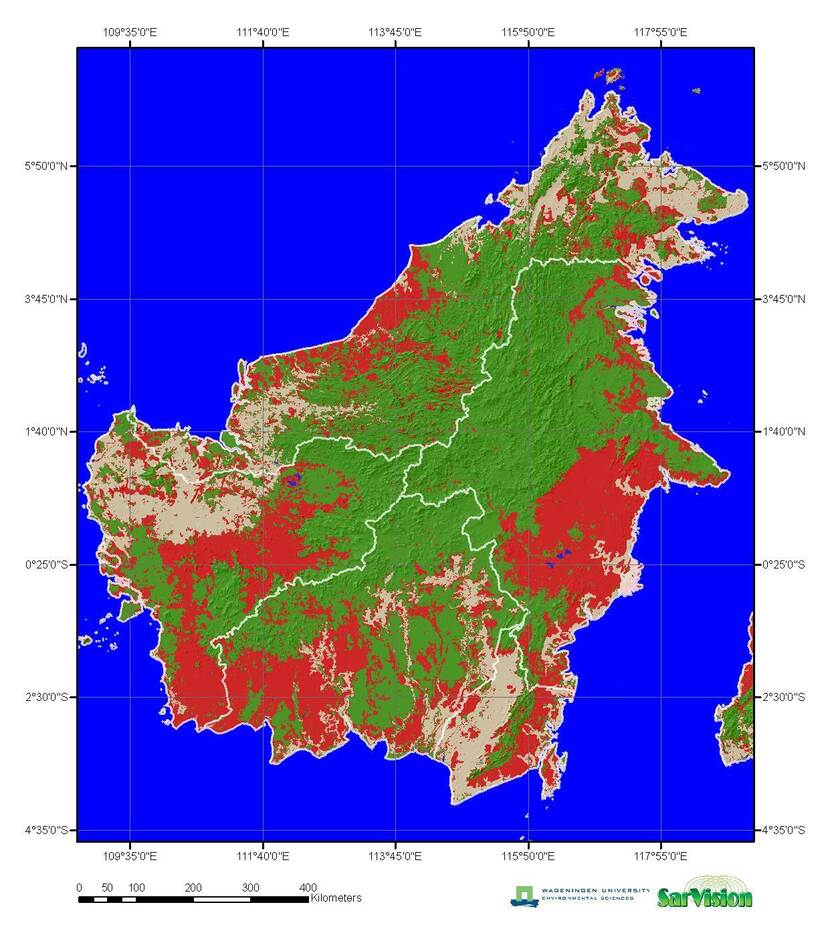

For now, the Netherlands is a leading provider of commercial services. ‘Historically, research institutes such as Wageningen University & Research and ITC Twente have amassed extensive knowledge in tropical forests and Earth observation. This knowledge development goes back thirty years. About twenty years ago, market demand arose, which led to start-ups. These start-ups were spin-offs from the universities that began developing and offering commercial services. We are still leaders in this field, although we feel the competition from other countries.’

SarVision is one such company. ‘SarVision mainly works with governments and NGOs like the World Wildlife Fund. They provide monitoring services and share their knowledge with governments. With a recent innovation, partly developed within an ESA program, even forest degradation can be monitored. This includes accurate detection of small-scale selective logging and forest encroachment.’

Satelligence provides services for market parties. ‘Thanks to partners and an impact investor, the company has grown from three to nearly forty employees in five years. These services for deforestation and risk profiling were developed within an ESA program and subsequently adapted to meet the EUDR requirements.’

And there are even more inspiring examples. ‘Space4Good, S&T, and NEO have also developed services to monitor deforestation. Meridia and AKVO have extensive experience in mapping the boundaries of agricultural plots in developing countries.’

‘Will it be easy to trace the origin of raw materials in twenty to thirty years? I tend to say: yes.’

The future of satellite observation

Will it be easy to trace the origin of raw materials in twenty to thirty years? ‘Well, so much happens over several decades that it’s hard to predict anything. But I tend to say: yes, it can. Future technology will become cheaper over time, and more training data will become available for developing AI algorithms. At NSO, we are proud of what we have achieved in the Netherlands, and we hope to stay ahead of the competition in terms of quality and price.’

More information

For more information please go to the NSO online or contact the NSO directly.